Wilhelm Fuchs (some times erroneously listed as "Wilhelm Fried") was born on the very first day of 1879 in the town of Tulchva in what was then Austria-Hungary. His parents were German Jews who brought their young son to America when he was only nine months old. Somewhere along the way, Wilhelm's name was changed to William Fox, a direct English translation of his Germanic name. This most likely occurred when his parents immigrated to the United States, as it was fairly common practice for immigration officials to enter into their books Americanized versions of European names. It is not documented when Wilhelm became William, but "Americanization" is the most likely reason.

William was the eldest of a family of 13 children. Only six of his brothers and sisters survived childhood. Fox grew up in New York City's Lower East Side. Fox left school at the age of eleven to go to work, which was not an uncommon thing for children of that era. He worked hard and was quickly making a modest living in the fur and garment business. At the age of 20, Fox married 16-year-old Eve Leo on December 31, 1899. He claimed this timing was most efficient, allowing him to celebrate his anniversary, his birthday, and New Year's all at once.

He

started

his own fur business in 1900, which he sold in order to start the Greater New

York Film Rental Company in 1904 with the purchase of a run-down

Nickelodeon in Brooklyn. As the new owner with an empty house, Fox

hired a coin manipulator and a barker to attract patrons into the dark

146-seat theater. Once audiences adequately understood what moving

pictures were, live acts were dispensed with. More theaters were

opened and he became a successful film exhibitor.Fox opened a

projection style theater at New York's 700 Broadway during May 1906.

With its success, he purchased more Nickelodeons and converted them into theaters.

He

started

his own fur business in 1900, which he sold in order to start the Greater New

York Film Rental Company in 1904 with the purchase of a run-down

Nickelodeon in Brooklyn. As the new owner with an empty house, Fox

hired a coin manipulator and a barker to attract patrons into the dark

146-seat theater. Once audiences adequately understood what moving

pictures were, live acts were dispensed with. More theaters were

opened and he became a successful film exhibitor.Fox opened a

projection style theater at New York's 700 Broadway during May 1906.

With its success, he purchased more Nickelodeons and converted them into theaters.

With his fledgling chain of theaters, Fox fought against the movie monopoly of the Motion Picture Patents Company owned by Thomas Edison. The fight ended in 1912 when the Supreme Court rules in Fox's favor. Fox then founded Fox Films, which on average produced four feature films a year. Four years later, the company moved to 13 acres in Hollywood California, where many movie companies were relocating. Operations of Fox's exploding empire were consolidated into the Fox Film Corporation in 1915. It was composed of the Fox Hollywood studios and the Fox Theatre chain.

Fox Films were wildly successful and very profitable. A series of Westerns staring film idol Tom Mix grossed almost $1 million per film for Fox. Fox made the first manufactured movie star, Theodosia Goodman from Cincinnati. Fox renamed his star "Thesa Bara", which was publicized as being an anagram for "Arab Death", she was already called Theda (a common nicname for Theodosia at the time). Arab Death was a perfect antidote for Mr. Bara's characters as she often played a dubious seductress or vamp. In her most famous movie, "A Fool There Was", her character, the "Vamp", whispered the immortal line, "Kiss me, my fool"! The photo to the right is of Ms. Bara as Cleopatra in the 1917 film of the same name. William Fox was credited with directing Cleopatra himself.

Fox began

to build the famed Fox Hills Studios on 100 acres just outside

Hollywood in 1923. Fox Films were wildly popular and very financially

profitable, if something less than artistic masterpieces.

Fox began

to build the famed Fox Hills Studios on 100 acres just outside

Hollywood in 1923. Fox Films were wildly popular and very financially

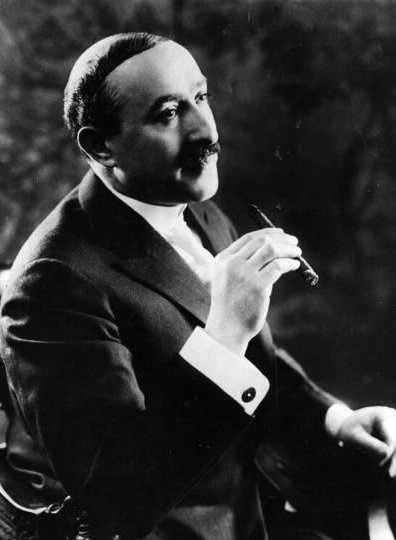

profitable, if something less than artistic masterpieces.  W.F., as he was addressed, was a publicity-shy man, called

in the press "a brilliant, excited, energetic, roughneck."

His niece, Angela Fox Dunn, recalls her Uncle Bill was given the

title "The Lone Eagle of the Film Industry".

At the height of his empire building, Fox was known never to carry

anything smaller than a $100 bill. He refused to wear a watch

and always kept his office blinds drawn in an effort to make time

stand still. His personal motto was "the day ended when the work is

done". For a period of almost 25 years, from 1904 until 1929,

the Fox fortunes improved steadily with no signs of slowing down.

At his zenith, Fox and his corporation owned a third of all the movie

theaters in the world. Fox once boasted "No second of every 24

hours passes but

that the name of William Fox is on the screen in some part of

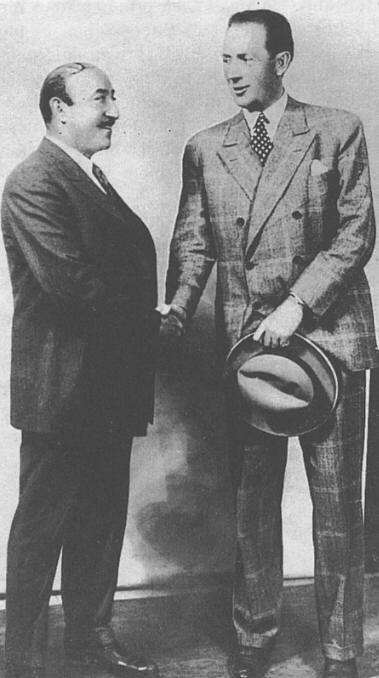

the world!" The image to the right of this text depicts

W.F. Fox with the famous Geraman filmmaker F.W. Murnau taken around

1926.

W.F., as he was addressed, was a publicity-shy man, called

in the press "a brilliant, excited, energetic, roughneck."

His niece, Angela Fox Dunn, recalls her Uncle Bill was given the

title "The Lone Eagle of the Film Industry".

At the height of his empire building, Fox was known never to carry

anything smaller than a $100 bill. He refused to wear a watch

and always kept his office blinds drawn in an effort to make time

stand still. His personal motto was "the day ended when the work is

done". For a period of almost 25 years, from 1904 until 1929,

the Fox fortunes improved steadily with no signs of slowing down.

At his zenith, Fox and his corporation owned a third of all the movie

theaters in the world. Fox once boasted "No second of every 24

hours passes but

that the name of William Fox is on the screen in some part of

the world!" The image to the right of this text depicts

W.F. Fox with the famous Geraman filmmaker F.W. Murnau taken around

1926.

Seeing the writing on the wall, William Fox worked to bring sound to

his studio long before the The Jazz Singer was made. Between 1925

and 1926, Fox purchased the rights to the work of Freeman

Harrison

Owens as well as the United States rights to the Tri-Ergon system

invented by three Germans. Taking those two technologies and

combining it with the work of Theodore Case, Fox's

company created

the Fox Movietone sound-on-film system. This system

incoporated information bands directly on the side edge of the film

celluloid. The bands were read by an optical device connected

to

the projector that converted the information to sound and

then sent the signal to amplifiers and out to

the speakers in the auditorium. Movietone was in wide release

for public

use in

1927, primarily for the Fox Movietone News weekly newsreels. Fox debuted MovieTone to the public with the release of

F. W. Murnau's Sunrise. in the picture on the right, Fox is seen shaking hands with Murnau.

Seeing the writing on the wall, William Fox worked to bring sound to

his studio long before the The Jazz Singer was made. Between 1925

and 1926, Fox purchased the rights to the work of Freeman

Harrison

Owens as well as the United States rights to the Tri-Ergon system

invented by three Germans. Taking those two technologies and

combining it with the work of Theodore Case, Fox's

company created

the Fox Movietone sound-on-film system. This system

incoporated information bands directly on the side edge of the film

celluloid. The bands were read by an optical device connected

to

the projector that converted the information to sound and

then sent the signal to amplifiers and out to

the speakers in the auditorium. Movietone was in wide release

for public

use in

1927, primarily for the Fox Movietone News weekly newsreels. Fox debuted MovieTone to the public with the release of

F. W. Murnau's Sunrise. in the picture on the right, Fox is seen shaking hands with Murnau.  The

year

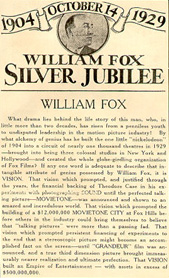

of 1929 was pivotal for William Fox. By then, he had parlayed

his initial investment of $1,660.67 for a 146-seat Brooklyn storefront

Nickelodeon theatre into a nationwide circuit of 1100 theatres.

The Fox Theater chain had been continuing to build more and

more opulent

movie palaces. In 1929, the most opulent of them all, dubbed the Super-Foxes in Detroit, St. Louis,

San Francisco, and Atlanta opened.

The

year

of 1929 was pivotal for William Fox. By then, he had parlayed

his initial investment of $1,660.67 for a 146-seat Brooklyn storefront

Nickelodeon theatre into a nationwide circuit of 1100 theatres.

The Fox Theater chain had been continuing to build more and

more opulent

movie palaces. In 1929, the most opulent of them all, dubbed the Super-Foxes in Detroit, St. Louis,

San Francisco, and Atlanta opened.

On March 3rd of 1929, Fox shook the film industry by announcing his attempt to takeover the Loew's Corporation. Loew's Inc. President Nicholas Schenck agreed to sell a controlling interest in the firm to Fox Film Corp. for $10 million. That would have given Fox control of Loew's theater chain and its MGM studio subsidiary, but Fox wanted complete control.

The driving reason for Fox's purchase of Loew's, Inc. was that he wanted to thwart Adolph Zukor, the primary owner of Paramount Pictures, from aquiring Loew's. Fox claimed that the late Marcus Loew (who died unexpectedly in 1927) and Zukor, who had been partners in vaudeville, had a gentleman's agreement in which their theater chains would only show each other's films and keep out other studios' pictures. Acquiring Loew's would allow Fox to release his pictures in the Loew's theater chain and force out Paramount films, thus giving him a competitive edge over Zukor and Paramount. Fox made an agreement with Schenck by which the Loew's boss would assemble enough shares of stock, in secret, to give Fox control. The $10-million price included a $2.5-million premium for Schenck.

Fox planned to merge MGM with his own studio, a merger that would require the approval of the Justice Department's Anti-Trust Divison, which Fox expected would approve the deal despite the huge concentration of production and power it would put in the hands of one man and a single studio. Fox lobbied the government in order to try to get the deal pushed through. When MGM studio boss Louis B. Mayer got wind of the deal, he used his connections with the administration of US President Herbert Hoover to block and delay the deal, in order to protect himself from being forced out from his own company as had happened to other studio moguls in the past. The most notable was Samuel Goldwyn, who had been squeezed out of both Paramount Pictures and his own Goldwyn Studios (which later became a part of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer). Fox had made the tactical error in trying to keep L.B. Mayer in the dark, and he tried to rectify that mistake by offering Mayer $2 million. Although Fox's political clout got him in to plead his case to President Hoover, Mayer's political connections proved to be the stronger. After at first seeming to go along with the Loew's acquisition, the Justice Department reversed course and filed an anti-trust suit against Fox. Fox's plan was finally thwarted when his creditors began to make financial demands for repayment. He owed more than $50 million for Fox Studio expansion and the retrofitting of his theaters for sound.

Personal tragedy struck in late July when an auto

accident

killed the family chauffeur and seriously injured William Fox.

He was still recuperating when

the stock market

crash on October 29, 1929 (Black Tuesday) marked the start of the Great

Depression. The

stock market crash left him with virutally no cash and

almost all of his assests were tied up as collateral for what was

now worthless stock. In a matter of weeks, Fox went from a man

whose

worth was valued at

over $400 million to one that was nearly $100 million in

debt. A headline of December

6 that read, "Stock Market

Crash Traps Movie Czar in $91,000,000 Debt."

signaled

the collapse of the Fox Empire.

Personal tragedy struck in late July when an auto

accident

killed the family chauffeur and seriously injured William Fox.

He was still recuperating when

the stock market

crash on October 29, 1929 (Black Tuesday) marked the start of the Great

Depression. The

stock market crash left him with virutally no cash and

almost all of his assests were tied up as collateral for what was

now worthless stock. In a matter of weeks, Fox went from a man

whose

worth was valued at

over $400 million to one that was nearly $100 million in

debt. A headline of December

6 that read, "Stock Market

Crash Traps Movie Czar in $91,000,000 Debt."

signaled

the collapse of the Fox Empire.

By early 1930, William Fox was leveraged out of his CEO position of Fox Film Corporation Fox was forced to sell its Fox Films Studio to bankers for $18 million. One of the last films produced by Fox at Fox was 1930's The Big Trail, John Wayne's first leading role and the first domestic widescreen movie. By the end of 1930, trying to salvage what it could, most of the company's Fox Theaters were handed over to Loews, Inc. in an attempt to settle the debt owed by William Fox's failed takeover attempt. In 1932, Fox Film Corporation filed for bankruptcy protection, like a lot of other movie studios, in an attempt to reorganize and recover that did not succeed. In 1935 the Fox Film Corporation, under the direction of its president Sidney Kent, was sold to Darryl F. Zanuck who decided to merge it's assets with his own Twentieth Century Films production company to form Twentieth Century - Fox Films. (Note the hyphen in the name. It was meant to distinguish the two studios from each other.) The newly merged company had Joseph M. Schenck as its president. Joe Schenck's brother, Loew's President Nick Schenck, partially financed the deal.

While William Fox was no longer directly involved with any film studio, he was making money from the royalties he was personally earned through the licensing deals he had made for his movie and sound patents. This revenue was not enough to keep Fox's personal finances solvent and in 1936 his bank accounts were completely depleted. Fox was forced into personal bankruptcy. Through the bankruptcy process of auctioning off any of his pocessions that had value in order to pay his creditors, Fox lost most, but not all of his patents.Fox and his family was kept financially secure thanks to the his patent holdings he was able to retain after the bankruptcy. This allowed Fox and his family to live in relative comfort. On May 8, 1952, with a reported estimated personal fortune of $20,000,000, William Fox died as "The Film Industry's Forgotten Man" in New York City. Fox's death certificate lists his real name as "Wilhelm Fuchs". The industry that he helped to found did not officially recognize or commemorate his passing. One of the few tributes to his life was William Fox listed under "Nobel Prize Winners and Famous Hungarians" although he is neither a recipient of a Nobel Prize nor Hungarian.

While Fox died

a forgotten man, his legacy continues to live on in the form of

the Twentieth Century-Fox Studios. The studio introduced the

CinemaScope

panoramic format in 1953 with its release of The Robeto

compete with the growing impact of television on dwindling

theater attendance. In time, the hyphenated name lost its hyphen and

more emphasis was given to the Fox name. The studio name will forever

be associated

with such stellar recent movies as Cleopatra, The Sound of Music, and the six original Star

Wars movies. Its opening "Fox Fanfare" theme

is one of the most widely recognized anthems in the world today.

While Fox died

a forgotten man, his legacy continues to live on in the form of

the Twentieth Century-Fox Studios. The studio introduced the

CinemaScope

panoramic format in 1953 with its release of The Robeto

compete with the growing impact of television on dwindling

theater attendance. In time, the hyphenated name lost its hyphen and

more emphasis was given to the Fox name. The studio name will forever

be associated

with such stellar recent movies as Cleopatra, The Sound of Music, and the six original Star

Wars movies. Its opening "Fox Fanfare" theme

is one of the most widely recognized anthems in the world today.

In 1985 the Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation (now minus the hyphen) became a division of News Corporation owned by Rupert Murdoch and was simply renamed Fox, Incorporated. Ironically, the film production unit was renamed the Fox Film Corporation in 1989, the original name that Fox gave his new movie studio in 1915. Despite the name change, 20th Century Fox still appears on the opening titles of films and television programming it distributes.

Fox's legacy also survives through the remaining Fox Theatres that are spread across the United States. While the vast majority of Fox Theatres have been razed, including the spectacular San Francisco Fox, theatres in Detroit, St. Louis, Atlanta, Redwood City, Boulder, Bakersfield, Oakland, Visalia, and others that bear William Fox's name continue to pay tribute to him and the empire he established in the early days of cinema.