A History of the American Movie Palace

By Hal Doby, originally written in 1996, last revision February 2013..

In

the begining, "Moving Pictures", now more commonly known as Motion

Pictures or simply "The Movies" were developed by many people in

many countries with the

major innovators being in the United States and France. Here in the

United States,

moving pictures were mainly pioneered by Thomas Edison's company, best

known for

his development of the electric light bulb and phonograph. His

company was the first to demonstrate moving pictures to the public

in the Americas. His

early experiments followed the same pattern as his phonograph,

with the pictures recorded on to a wax cylinder.

In

the begining, "Moving Pictures", now more commonly known as Motion

Pictures or simply "The Movies" were developed by many people in

many countries with the

major innovators being in the United States and France. Here in the

United States,

moving pictures were mainly pioneered by Thomas Edison's company, best

known for

his development of the electric light bulb and phonograph. His

company was the first to demonstrate moving pictures to the public

in the Americas. His

early experiments followed the same pattern as his phonograph,

with the pictures recorded on to a wax cylinder.

As an historical

note, Edison did not work alone. He had other scientists and engineers

working with him in his laboratory and while a lot of Edison's

inventions and technologies were directly credited to Edison himself,

there were others who rightfully deserved credit that went un-named.

In 1889, Edison handed the development of the moving pictures

project to a young Scotsman named William Kennedy Laurie Dickson.

Dickson stopped working with cylinders and began work on a system

that used strips of celluloid film, the same material that was

being developed for still photography.

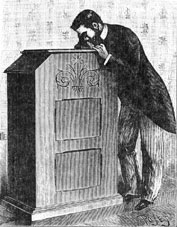

Dickson's camera was called the Kinetograph. It used rolls

of film about 35mm wide with rows of holes down the sides to allow

the film to be pulled through the camera at an even rate by gears.

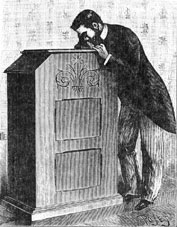

At the same time, Dickson developed a viewer for the films that

was called a Kinetoscope. One person at a time would look through

the viewing piece at the top of the box. The film ran through

a series of pulleys in a continuous loop, so that it could be

watched over and over again without rewinding.

Thomas Edison was renown for applying for patents for anything his

team of engineers designed. He wisely knew that should any of their

innovations become popular or useful, those patents would then require

anyone that used anything derrived from those patents, would owe Edison

a royalty fee. Also through those patents, Edison could control who,

how, when, and why those innovations were used. This has

made Edison a millionair through his patents for Electricity, the light

bulb and the phonograph. Now Edison was looking to make millions

through the control of the fledling film industry.

Edison's earliest

films lasted for about 20 seconds or less because of the amount

of film you could put into the camera. They were first demonstrated

to the public in 1893 at the Chicago World's Fair. By the following

year, a "Kinetoscope Parlor" opened in New

York, with ten machines showing different films. At right is an

early Edison film from the same time period that has been converted to an animated

GIF. "The Sneeze" is presented here uncut in its full

length to show you just how short "short" was back then.

Edison's earliest

films lasted for about 20 seconds or less because of the amount

of film you could put into the camera. They were first demonstrated

to the public in 1893 at the Chicago World's Fair. By the following

year, a "Kinetoscope Parlor" opened in New

York, with ten machines showing different films. At right is an

early Edison film from the same time period that has been converted to an animated

GIF. "The Sneeze" is presented here uncut in its full

length to show you just how short "short" was back then.

In order to understand the attraction to viewing these short

films, you have to remember that at the beginning of the 20th

century, the common person did not travel more than 25 miles away

from where they were born. Their life experiences were limited to

the things that were commonplace in their small communities. Things that

were not in their small part of the world were often considered to be very exotic and it

was exciting to see those things that were not part of their every day worlds. No

one had seen moving pictures before, so even a few moments of

action was astounding. The first films were very short and most were what was termed

Real Life Studies. Animals, city life, and the new modern wonders

such as the aeroplane and the horseless carriage were common subjects.

People who saw those films were voracious in their appetite to

see more to know more about the world around them.

As the technology

progressed and longer moves could be made, they began to tell

short stories, but even then, they lasted just a few minutes in length. Kinetoscope parlors

sprang up all over the country and rows of Kinetoscopes were added

to existing entertainment venues like penny arcades. Operators

attempted to attract customers through sidewalk barkers and displays set up in their

wide entranceways.

It became an

enduring feature of movie theater construction still employed

today.

As the technology

progressed and longer moves could be made, they began to tell

short stories, but even then, they lasted just a few minutes in length. Kinetoscope parlors

sprang up all over the country and rows of Kinetoscopes were added

to existing entertainment venues like penny arcades. Operators

attempted to attract customers through sidewalk barkers and displays set up in their

wide entranceways.

It became an

enduring feature of movie theater construction still employed

today.

While Edison's invention was very prolific in the United States, In

Europe, Auguste and Louis Lumière became the European leaders in

the technical art of cinema. Unlike Edison, the brothers worked on the concept of

presenting thier films by a projector that projected the image on to a

large screen so a multitude of people could view a film at the same

time instead of one person at a time by looking into a Kinetoscope. The

Lumières held their first private screening of projected motion

pictures in 1895. Their first public screening of films at which

admission was charged was held on December 28, 1895, at Salon Indien du

Grand Café in Paris. This history-making presentation featured

ten short films, including their first film, Sortie des Usines

Lumière à Lyon (Workers Leaving the Lumière

Factory). Each film was 17 meters long, which, when run through a hand cranked projector, ran approximately 50 seconds.

When the Lumiere Brothers projection system came to America, the

Kinetoscope was quickly replaced in favor of the projection system

which is still in use today. Film exhibitioners preferred

presenting a single film

to a mass audience because simplification meant a lot more profit

was to be made. Gone were rows of expensive machines that had to

be individually maintained and each provided with a copy of a

film. In

their place was a single projector, one screen, and one film.

As these film theaters became commonplace, they were quickly

named. Nickelodeons. The term was derrived by combining the word

"Nickel",

the price of admission, with "Odeon," the ancient name

of Grecian theaters.The first Nickelodeon opened in Pittsburgh in 1905 (as shown

on the photo) when the proprietors of the Smithfield

Street movie house renamed their theaters Nickelodeons.

In 1904, a 24-year-old William Fox started the Greater New

York Film Rental Company with the purchase of a run-down Nickelodeon

in Brooklyn. With its success, he purchased more Nickelodeons.

As his fledgling chain of theaters began to grow bigger, Fox began to fight against the controlling

monopoly of the Motion Picture Patents Company owned by Thomas

Edison. Edison held his film patents tightly and using his power and

his company's vast financial resources, Edison's Kinetoscopes

dominated the American market. After long and heated court battles, Edison's monopoly came to an end in

1912 when the Supreme Court ruled in favor of William Fox.

The

age of the kinetoscope not only coming to an end as once Edison's

monopoly was broken, other entrepreneus almost overnight began to

establish new motion

picture studios.

Where Kinetoscopes were limtied to showing a film of a certain

length, projectors did not have this limitation. They could hold

as

much film as the bighest real used. During the time of the

Kinetoscopes, most films

were shot continuously. Any "editing" was done by turning the

camera on or off. Rarely were films were actually edited and

spliced together at the studio level. Around

the same time the Kinetoscopes were loosing popularity, filmmakers

began in earnest to

tell stores. To aid in their story telling, they began to make multiple

"takes" of scenes, then through editing and using multiple film

elements they were able to present more and more elaborate

stories. This was the beginning of the modern film.

Theater-goers began to enjoy two types of films. The traditional

"short-form" ran anywhere from a few minutes to about 20 minutes

in length. This was joined by a much longer

"feature film" that on average ran approximately 80 minutes or

longer. Going to the theater, even though it was relatively

cheap, was a big deal and theater operators had to present a program of

films that they felt gave the customer value for their five cents. News

organizations came up with the idea of taking film cameras to

record important

events and other news-worthy stories and they were put together as

weekly newsreels. By the early 1920s, the traditional movie

presentation had patrons watching one or two short films, a

current newsreel, trailers of upcoming films, and then finally the

feature film would conclude the program. All told, a viewing could last

three to four hours.

The first "theaters" were very simple and plain. They were usually

very spartan, smoke-filled,

and incredibly dingy. They were nothing more than simple rooms or store

fronts that had either a white-washed wall or a linen sheet hung

up on a wall to act as a screen. The chairs were loose and placed

into rows to suit the room. In the middle or rear of the room

sat the projector with its operator, who might also act as the

ticket vendor. Accompanying the film, was a piano, often played

by a girl or woman from the neighborhood, using whatever music

she had in her repertoire at the moment. Still, for a nickel you

could be transported into a fantasy world on the screen. The theaters

often included other attractions such as illustrated

song slides, song and dance acts, comedy, live dramas and other

features that allowed them to compete with vaudeville houses.

Theaters happily operated like this for almost two decades because

of the low-cost of operation. The popularity of these affordable,

entertaining,

and highly profitable venues was such that their numbers mushroomed

to approximately 8,000 in the United States by 1908.

Attendance was growing from a few people into the hundreds and

eventually thousands

at a time. Because of the growing number of patrons, the old ways of

showing films were

beginning to have serious safety considerations. New local and

federal public safety laws were made that started to have a direct

bearing on

the theaters and their operation. In the theaters,

should

there be a crisis, people could

panic with no regard for others and rush to the front doors. Chairs and

furnishings would

be tossed about and the human stampedes would cause as much injury

or death as the event that sparked the crisis. Fire was the number

one threat. Stage lights, the abundance of people smoking, and

the flammable nitrate-based films themselves were all serious risks that could result in disaster.

The average building could go up in flames very quickly.

With the new laws established, film exhibitors could no

longer convert a store front into a theater. The new entertainment

wonder had to evolve. The "next-generation" theaters often began as failed

opera houses, concert halls, or churches that were more readily

converted into theaters. The popularity of the

motion pictures was so great, pretty soon all of the available

buildings with some form of an auditorium were taken and demand

was still not satisfied. Even larger auditoriums were needed and

with the new safety rules it began to make much more economic sense to

construct new buildings instead of attempting to renovate

an existing structure. The new buildings would incorporate safety

features such as emergency exits, fire-retardant construction materials, and a separate projection room that separated

the equipment and the very 3 ew flammable film from the rest of the structure. Smoking

in the auditoriums was also banned as a further safety measure.

Motion Picures were not well

regarded

by upper society. Because of its popularity by "the common man" and

its origins in what many considered to be sleazy Nickelodeons or

"Flea Pits", the

members of upper society considered the "flickers" low-brow

entertainment. Yet, the pioneers of cinema had

become self-made multi-millionaires almost over night. Like a lot of

people that become wealthy through hard work instead of inheritance, it

became important to film's pioneers to make their industry

acceptable to

the members of high society while at the same time incease their appeal

to the common patron that made them wealthy in the first place. It

was hoped that someday the

fledgling industry would be held in the same high regard as

what other considered to Fine Arts; Dramatic Performance/Theater,

Ballet, Symphony, and Opera.

The first major step to that goal was taking the movies out of the

"flea pits"

and placing them into proper theaters that befitted the patronage

of refined gentlemen and ladies. Moving into

converted opera houses and purpose-built theaters did a lot to achieve

that

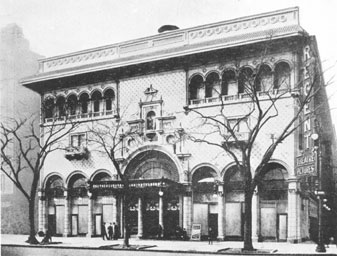

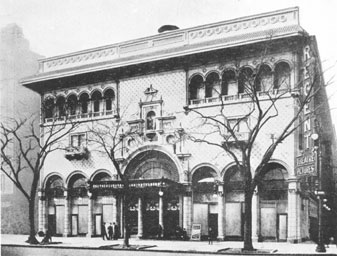

goal. Built in 1902, Tally's "Electric" Theatre in Los Angeles (shown at left) was

the first permanent structure devoted entirely to movies. Audiences immediately preferred the

comfortable, clean, and well-appointed surroundings of a proper

theater. They theaters also featured better-quality musical

accompaniments and even well-dressed ushers to assist patrons.

The first major step to that goal was taking the movies out of the

"flea pits"

and placing them into proper theaters that befitted the patronage

of refined gentlemen and ladies. Moving into

converted opera houses and purpose-built theaters did a lot to achieve

that

goal. Built in 1902, Tally's "Electric" Theatre in Los Angeles (shown at left) was

the first permanent structure devoted entirely to movies. Audiences immediately preferred the

comfortable, clean, and well-appointed surroundings of a proper

theater. They theaters also featured better-quality musical

accompaniments and even well-dressed ushers to assist patrons.

While this was decades away from the Great Depression, life was much more

hard than people know it to be in the 21st century. People loved

escaping their harsh worlds by getting involved in the stories this

new modern marvel told. Entrepreneurs soon caught on to the

idea of extending the fantasy world from just the screen image

to the whole experience of going to the movies. New movie theaters

were built not only to hold larger audiences, but their entire scale

and grandeur was put into overdrive. Because of these buildings

having such opulence and extraordinary architectural beauty, a

new term was coined. These were not mere theaters, they were Palaces where the average patron would be treated as

royalty. The Movie Palaces were such a commercial success, between

1914 and 1922, 4,000 Movie Palaces opened in the United States with many more to come.

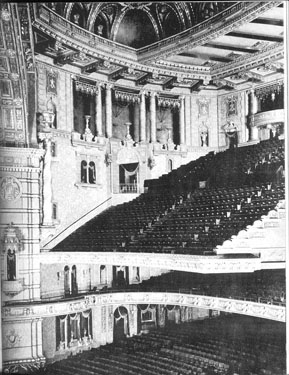

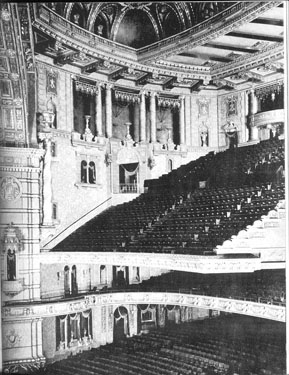

The

Regent (shown at left) was acknowledged as America's first motion picture

palace. Built for and operated by Jacob Fabian, it opened in Paterson,

New Jersey on September 14, 1914. The Regent was located

in a working class neighborhood up-town from the "legitimate" theater

district and stood between Old Union Street (which was later renamed

World Vet's Place in 1959) and Hamilton Street. As it was being

constructed, a majority of people believed that the huge cost of the

building's construction would prove to be a great liability. To that

end, it was oftern referred to as "Fabian's Folly" during the early

days, but once the theater was open and operating, the Regent proved

all of its ney-sayers to be wrong. A reporter for the Motion Picture

News declared that

the opening night audience "was the kind to be found at the

best playhouses. Judged by their decorum and sincere appreciation,

they might have been at the opera." Indeed, going to the

movie had gone from plopping down on a chair with a beer stein

in one hand and your cigar in the other, to putting on your finest

wardrobe to see and be seen alongside society's finest.

The

Regent (shown at left) was acknowledged as America's first motion picture

palace. Built for and operated by Jacob Fabian, it opened in Paterson,

New Jersey on September 14, 1914. The Regent was located

in a working class neighborhood up-town from the "legitimate" theater

district and stood between Old Union Street (which was later renamed

World Vet's Place in 1959) and Hamilton Street. As it was being

constructed, a majority of people believed that the huge cost of the

building's construction would prove to be a great liability. To that

end, it was oftern referred to as "Fabian's Folly" during the early

days, but once the theater was open and operating, the Regent proved

all of its ney-sayers to be wrong. A reporter for the Motion Picture

News declared that

the opening night audience "was the kind to be found at the

best playhouses. Judged by their decorum and sincere appreciation,

they might have been at the opera." Indeed, going to the

movie had gone from plopping down on a chair with a beer stein

in one hand and your cigar in the other, to putting on your finest

wardrobe to see and be seen alongside society's finest.

Another

form of public entertainment was what was known as

Vaudeville. Vaudeville was a live performance theatrical genre of

variety entertainment

in the United States and Canada from the early 1880s into the early

1930s. Each performance was made up of a series of separate, unrelated

acts grouped together on a common bill. Types of acts included popular

and classical musicians, dancers, comedians, trained animals,

magicians, female and male impersonators, acrobats, illustrated songs,

jugglers, one-act plays or scenes from plays, athletes, lecturing

celebrities, minstrels, and movies. Vaudeville developed from many

sources, including the concert saloon, minstrelsy, freak shows, dime

museums, and literary burlesque. Called "the heart of American show

business," vaudeville was one of the most popular types of

entertainment in North America for several decades. Most performers and

artists joined travelling Vaudeville

troops and they traveled from town to town, but a few continually

performed in

one location. A few performers gained what today we would call

"superstar" levels of popularity and they would strike out on their own

to travel around the country. As film's popularity exploded, it

had a direct and

very negative effect on Vaudeville and in by the 1930s, Vaudeville was

almost

completely put out of business.

Another

form of public entertainment was what was known as

Vaudeville. Vaudeville was a live performance theatrical genre of

variety entertainment

in the United States and Canada from the early 1880s into the early

1930s. Each performance was made up of a series of separate, unrelated

acts grouped together on a common bill. Types of acts included popular

and classical musicians, dancers, comedians, trained animals,

magicians, female and male impersonators, acrobats, illustrated songs,

jugglers, one-act plays or scenes from plays, athletes, lecturing

celebrities, minstrels, and movies. Vaudeville developed from many

sources, including the concert saloon, minstrelsy, freak shows, dime

museums, and literary burlesque. Called "the heart of American show

business," vaudeville was one of the most popular types of

entertainment in North America for several decades. Most performers and

artists joined travelling Vaudeville

troops and they traveled from town to town, but a few continually

performed in

one location. A few performers gained what today we would call

"superstar" levels of popularity and they would strike out on their own

to travel around the country. As film's popularity exploded, it

had a direct and

very negative effect on Vaudeville and in by the 1930s, Vaudeville was

almost

completely put out of business.

But as theaters moved into purpose-built houses, most were able to

accomodate live performances and that allowed theater owners to offer a

split bill of both film and Vaudeville performances.Vaudeville circuits

groups like Keith-Albee became

absorbed into motion picture corporations such as RKO

(Radio-Keith-Orphieum). Thier performers not only continued to perform

live, but also began to work as actors in films.

After dominating

the motion picture industry at the beginning of the century, Edison's monopoly gave way

to a handful of film companies that rapidly achieved what they called "Vertical

Integration" of the industry. The film studios controlled every aspect of the

"product" they manufactured. The studio "owned"

the players and film production teams by contract; they controlled

the subject matter and the owned the final product. Once it was

made, the studio would then self-promote the film and distribute

it to be shown at theaters that were mainly wholly owned by the same

studio.

It became increasingly harder for individual independent

entrepreneurs

to show new first-run films because none of the

studios would allow their films to be shown in theaters not owned

or in partnership with them. In the eyes of many, this had replaced

Edison's monopoly with other monopolies that forced almost all of

the

independent exhibitors to sign into a studio network agreement,

sell the theater to a studio, or close their doors. Of course,

legal challenges were filed, but it took almost 4 decades for

them to wind their way through the United States legal system

before the United States Supreme Court hear the case. .

As the legal challenges found their way to the highest court in the

land,

the damage had already been done. In a few short years the studios

totally

controlled movie production, distribution, and exhibition in the

U.S. The "Big Five" were Famous Players-Lasky (later

Paramount), Warner Brothers, Loew's / Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer,

Fox Films, and RKO. By 1929 Paramount operated

1200 theaters with Fox close behind at 1100. In 1930, the five

major film companies took in approximately 70% of all box office

receipts

in the United States.

Many of the studio heads, architects, and film exhibitors

were first-generation Americans. Among them were William Fox and

Samual Rothapfel, often called by his nickname "Roxy". Their

experiences as first-generation Americans might have given

them a different perspective on American consumer culture, but

instead they became some of its most ardent champions, and their

theaters became some of its most unforgettable monuments. Most

of  the great palaces were

designed and created by three architectural firms: Rapp and Rapp,

John Eberson, and Thomas Lamb for the "Big Five" studios. A healthy competition of sorts was had between the

three firms to see who could out do the others latest achievement.

Each new palace was becoming "the new modern wonder of the

world". Most movie palaces were built mainly employing themes from

Europe's grand architecture. The rule of thumb was the more ornate,

the better.

the great palaces were

designed and created by three architectural firms: Rapp and Rapp,

John Eberson, and Thomas Lamb for the "Big Five" studios. A healthy competition of sorts was had between the

three firms to see who could out do the others latest achievement.

Each new palace was becoming "the new modern wonder of the

world". Most movie palaces were built mainly employing themes from

Europe's grand architecture. The rule of thumb was the more ornate,

the better.

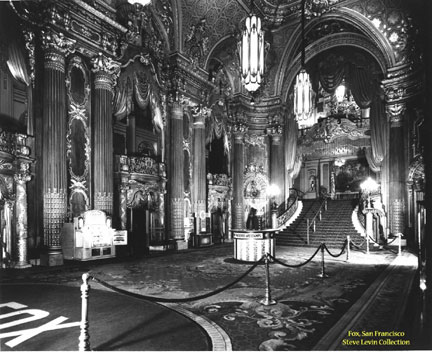

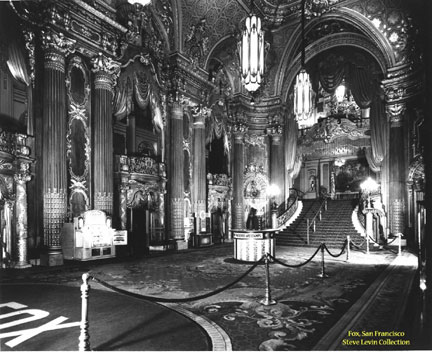

Everything about

the movie palace was designed to make the average citizen feel like a celebrity,

a millionaire, or royalty. When the San Francisco Fox (The exterior

is shown on the left while the lobby is depicted to the right)

opened in June of 1929, newspaper and magazine advertisements

proclaimed:

"No palace of Prince or Princess, no mansion of millionaire

could offer the same pleasure, delight, and relaxation to those

who seek surcease from the work-a-day world, than this, the Arcady

where delicate dreams of youth are spun...Here in this Fox dream

castle, dedicated to the entertainment of all California, is the

Utopian Symphony of the Beautiful, attuned to the Cultural and

Practical...No King...No Queen...had ever such luxury, such varied

array of singing, dancing, talking magic, such complete fulfillment

of joy. The power of this Purple we give to you...for your

entertainment.

You are the monarch while the play is on!"

Everything about

the movie palace was designed to make the average citizen feel like a celebrity,

a millionaire, or royalty. When the San Francisco Fox (The exterior

is shown on the left while the lobby is depicted to the right)

opened in June of 1929, newspaper and magazine advertisements

proclaimed:

"No palace of Prince or Princess, no mansion of millionaire

could offer the same pleasure, delight, and relaxation to those

who seek surcease from the work-a-day world, than this, the Arcady

where delicate dreams of youth are spun...Here in this Fox dream

castle, dedicated to the entertainment of all California, is the

Utopian Symphony of the Beautiful, attuned to the Cultural and

Practical...No King...No Queen...had ever such luxury, such varied

array of singing, dancing, talking magic, such complete fulfillment

of joy. The power of this Purple we give to you...for your

entertainment.

You are the monarch while the play is on!"

In large towns, it was common for more than one movie palace

to be built and it seemed where multiple theaters were, there

was a very healthy competition to make the next theater bigger,

better, and more over the top. Even in small cities and towns

where there was no direct competition, lavish theaters were erected

were citizens had never seen

such opulence. While not true "palaces", these theaters

were an important part of American culture. In the smaller towns,

movie theaters became cultural centers for their societies. Societal

life began to revolve around what was going on at the theaters.

In addition to the regular movies, the theaters would be rented out

for special events such as school graduations, traveling lectures,

community theater, and weddings. It was very common (and still

so today) for theaters to open their doors on Sunday mornings

to be used by church groups that didn't have their own sanctuary.

The Great Depression took its toll on the palaces. Theater

attendance dropped from 90 million per week in 1930 to 60 million

per week two years later when the Depression was at its worst. During the same period, the number of

operating theaters fell from 22,000 to 14,000. People were doing

good just to survive, and going to the movies became a rare luxury.

Theater managers had to trim their own operations just to keep

the doors open. The first thing to go was live acts.

They soon learned that by making the program shorter, they could

have more than one show a night, which meant more revenue. The standard

evening program had a newsreel, a cartoon, perhaps a short special

interest film, previews, and the feature. Weekend Matinees would

commonly add an episode of a serial adventure such as an adventure of

Buck Rogers, Flash Gordon, Roy Rogers, Batman, Tarzan, and Dick Tracy.

Another thing that might seem unbelievable today was the early

theaters did not have food concessions. Since the movies were trying to

emulate "The Arts", people simply did not eat or drink during

those performances, so why should going to this new art form be any

different? Some theaters allowed people to sell food and drinks

outside the theaters that people were allowed to bring in. Some patrons

actually

brought their own sandwiches or snack food with them from home. As the

exhibitors grew desperate for revenue, they realized that this was a

potentially vital stream of income they had not tapped into! In short

order, outside food and drink was banned as concession stands were

put into the theaters. By the late

20th Century, most exhibitors made the majority of their income at the

concession stand because most film distributors demand over 90% of the

money generated from ticket sales. (Editor's Note: This is why I always

make a point to buy popcorn and drinks in order to actually support my

local theater!)

Despite their best

efforts, many theaters did not make it and were boarded

up. San Francisco's Fox Theatre went dark in 1932, just three

years after it's opening, when Fox Films declared

bankruptcy. Thanks to William Fox's attempt to

control

Loew's Inc/MGM through the purchase of stock in a leverage buyout, it

was partly owned by Fox when Fox Studios went

into receivership. As part of the court negotiated liquidation of

Fox Films assets, Loew's Inc.eventually emerged from the Fox

bankruptcy owning a substanial part of the Fox Theater

chain. Fox Studios was sold and eventually merged

with Twentieth Century Studios. The new corporation was renamed

Twentieth Century-Fox (the hyphen is important!). In 1935. Famous

Players/Laskey fell into receivership in 1933, but it was

able to reorganize and it emerged from bankruptcy intact in

1936 as Paramount Pictures. RKO entered into

bankruptcy protection in 1934 and reorganized in 1939.

Universal sold its theaters as a stopgap measure but fell into

receivership in 1933. It emerged from reorganization in 1936.

Only Warner

Brothers, Columbia, and United Artists survived the Depression

without having to declare bankruptcy and their theater chains left

intact.

As the economy slowly recovered,

the picture palaces that survived the Great Depression began to

enjoy a renaissance but it was never to be as it was prior to 1929. The

Great Depression had a tremendous effect on the American Society well

beyond just the financial aspects of the stock market crash. From Black

Monday until mid-1932,

things went from bad to worse before improvements slowly began.

As the economy slowly recovered,

the picture palaces that survived the Great Depression began to

enjoy a renaissance but it was never to be as it was prior to 1929. The

Great Depression had a tremendous effect on the American Society well

beyond just the financial aspects of the stock market crash. From Black

Monday until mid-1932,

things went from bad to worse before improvements slowly began.

One

of the more recognized shifts occurred with the election of Franklin

Delano Roosevelt as President in 1932. As part of his election

campaign, he promised a "New Deal" to the American populace. With that,

Americans began to look towards an eciting new future and with that,

they abandoned a lot of the conventional perceptions of wealth and

luxury and moved towards a new asthetic. The opulant style old-world

European style quickly fell out of fashion. The ultra-modern style, now called Art Deco, was immediatley embraced.

Please Note: During the years when Art Deco was a fashion style, the term Art Deco was not used. The terms. Modernistic, Moderne,

or Style/Art Moderne referred to this style until the term Art Deco

was coined in the 60's by Bevis Hillier, a British art critic

and historian. He derrived the name Art Deco from the 1925 Exposition

Internationale des Arts Decoratifs Industriels et Modernes, held

in Paris, where the Moderne style was recognized as a unique art form, different from other

art forms/styles.

Although

Art Deco was originally started in Europe, it had greater achievement

in architecture and interior design in the United States and today

is pretty much recognized as an American art form. Art Deco was

derived from another artistic expression, Art Nouveau that developed

in the 1880s. Art Nouveau was a concerted attempt to create an

international style based on decoration. Art Nouveau designers

believed that all should work in harmony to create a "total

work of art," or Gesamtkunstwerk: buildings, furniture, textiles,

clothes, and jewelry all should conform those principles. Art

Deco first appeared in the 1920s. It is a "modernization"

of many artistic styles and themes from the past. You can easily

detect in many examples of Art Deco the influence of Far and Middle

Eastern design, Greek and Roman themes, and even Egyptian and

Mayan influence. Modern elements included echoing machine and

automobile patterns and shapes such as stylized gears and wheels,

or natural elements such as sunbursts and flowers. The modern

art movements of Cubism, Futurism, and Constructivism influenced

Art Deco; however, it also took some ideas from the ancient geometrical

design styles, such as Egypt, Assyria and Persia. Art Deco designers

use stepped forms, rounded corners, triple-striped decorative

elements and black decoration often. The most important

Art Deco element is that all elements are in simple

geometrical order. If one is looking for appropriate words to

describe overall Art

Deco as a design style, "simplistic", "streamline", and "speed"

come to mind. During the Great Depression, Art Deco buildings

had very little protruding ornamentation and have very flat,

streamlined

looks.

Architects and

builders constructed the last large movie palaces in the 30s

during the

Great Depression, but they were nothing like the palaces that were

built prior to 1929. Art Deco had replaced the previous ornate

styles

of architecture and it became the standard in movie theater

design. There

are a lot of views as to why the movie palace architects

made such a fast transition to Art Deco. My opinion is there

were two driving factors to adopt Art Deco. The

first reason is economical. It was a substantially simpler to

design

and a lot less expensive to construct. Secondly, after we

were plunged into the Great Depression which,

pardon the pun, was depressing, we longed for a bright new future.I do

not think

there has been any other period in the history of man where we

as a civilization have looked so forward to the prospects of a

wondrous future. The Moderne style was so new, it embodied the promise

of that bright and exciting future. The Moderne style WAS the future. It was the harbinger of that

incredible future. In my

opinion, the 1939 World's Fair in New York was the epitome of this

expression with the General Motors exhibition, the World of Tomorrow

literally at its pinnacle.

As the world recovered from the Depression and before War loomed on the

horizon, the old European ornate styles were considered very dated and

out of fashion. Moderne / Art Deco was en vogue and pointed the way

to the sleek new future that lay ahead.

The first

Art Deco palace was designed in 1930 by Marcus Priteca. It was the Hollywood

Pantages at Hollywood and Vine in Los Angeles. While many others

were built, without a doubt, the most famous

Art Deco theater, and undeniably the most famous existing movie palace

in the world, is Radio City Music Hall. More than 300 million

people have patronized Radio City to enjoy stage shows, movies,

concerts and special events. Everything about it is larger than

life.

The first

Art Deco palace was designed in 1930 by Marcus Priteca. It was the Hollywood

Pantages at Hollywood and Vine in Los Angeles. While many others

were built, without a doubt, the most famous

Art Deco theater, and undeniably the most famous existing movie palace

in the world, is Radio City Music Hall. More than 300 million

people have patronized Radio City to enjoy stage shows, movies,

concerts and special events. Everything about it is larger than

life.  Radio City Music

Hall opened on December 27, 1932. Donald Deskey designed the Music

Hall's interior spaces. In his design, Deskey chose elegance over

excess, grandeur above glitz. He designed more than thirty separate

spaces, including eight lounges and smoking rooms, each with its

own motif. Given "The Progress of Man" as his general

theme, he created a stunning tribute to human achievement

in art, science and industry. He made art an integral part of

the design, engaging fine artists to create murals, wall coverings

and sculpture; textile designers to develop draperies and carpets;

craftsmen to make ceramics, wood panels and chandeliers. Deskey

himself designed furniture and carpets, and he coordinated the

design of railings, balustrades, signage and decorative details

to complement the theatre's interior spaces. It remains an elegant,

sophisticated, unified tour de force.

Radio City Music

Hall opened on December 27, 1932. Donald Deskey designed the Music

Hall's interior spaces. In his design, Deskey chose elegance over

excess, grandeur above glitz. He designed more than thirty separate

spaces, including eight lounges and smoking rooms, each with its

own motif. Given "The Progress of Man" as his general

theme, he created a stunning tribute to human achievement

in art, science and industry. He made art an integral part of

the design, engaging fine artists to create murals, wall coverings

and sculpture; textile designers to develop draperies and carpets;

craftsmen to make ceramics, wood panels and chandeliers. Deskey

himself designed furniture and carpets, and he coordinated the

design of railings, balustrades, signage and decorative details

to complement the theatre's interior spaces. It remains an elegant,

sophisticated, unified tour de force.

Today Radio

City is now the largest remaining motion picture theatre in the

world today. Its marquee is a full city-block long. Its auditorium

measures 160 feet from back to stage and the ceiling reaches a

height of 84 feet. The walls and ceiling are formed by a series

of sweeping arches that define a splendid and immense curving

space. Choral staircases rise up the sides toward the back wall.

Actors can enter there to bring live action right into the house.

There are no columns to obstruct views. Three shallow mezzanines

provide comfortable seating without looming over the rear orchestra

section below. A huge proscenium arch that measures 60 feet high

and 100 feet wide frames the Great Stage. It is comprised of three

sections mounted on hydraulic-powered elevators. A fourth elevator

raises and lowers the entire orchestra. Within the perimeter of

the elevators is a turntable that can be used for quick scene

changes and special stage effects. The shimmering gold stage curtain

is the largest in the world. Audiences

have thrilled to the sound of the "Mighty Wurlitzer"

organ, which was built especially for the theatre. And what's

a show without special effects? Original mechanisms still in use

today make it possible to send up fountains of water and bring

down torrents of rain. Fog and clouds are created by a mechanical

system that draws steam directly from a Con Edison generating

plant nearby.

The

most grand and opluent Movie Palaces were built between 1928 and 1930.

Radio City is acknowledged as the last built. Because the very nature

of the film industry

had changed, so were the palaces. Since live attractions similar to

those of Vaudeville before the age of film were now going the way of

the dinosaurs, there was no longer any need for any backstage areas.

Since sound had elminated the need for live musical accompaniment, gone

were the pianos, organs, and orchestra pits. Back stage became nothing

more than a storage room or nothing but a wall. The size of the lobbies

and the lounges were also shrinking because people spent less time at

the theater. True lounges were replaced with simple restrooms.

By the 1940s, most theaters consisted of four areas: the lobby,

the

auditorium, the restrooms, and the office/projection/storage

rooms. Yet the movie theaters were still very important social

centers for thier communites. During World War II, movie theaters

hosted newsreels and war

bond drives, attracting patriotic and news-hungry Americans by

the millions, which hit an estimated post-Depression high of 85 million

patrons each week. Americans packed movie theaters

during the war.

The

most grand and opluent Movie Palaces were built between 1928 and 1930.

Radio City is acknowledged as the last built. Because the very nature

of the film industry

had changed, so were the palaces. Since live attractions similar to

those of Vaudeville before the age of film were now going the way of

the dinosaurs, there was no longer any need for any backstage areas.

Since sound had elminated the need for live musical accompaniment, gone

were the pianos, organs, and orchestra pits. Back stage became nothing

more than a storage room or nothing but a wall. The size of the lobbies

and the lounges were also shrinking because people spent less time at

the theater. True lounges were replaced with simple restrooms.

By the 1940s, most theaters consisted of four areas: the lobby,

the

auditorium, the restrooms, and the office/projection/storage

rooms. Yet the movie theaters were still very important social

centers for thier communites. During World War II, movie theaters

hosted newsreels and war

bond drives, attracting patriotic and news-hungry Americans by

the millions, which hit an estimated post-Depression high of 85 million

patrons each week. Americans packed movie theaters

during the war.

Because of war time rationing, a building ban stateside stopped

construction

of new theaters during World War II, then in 1943 a study commissioned

by the United States Navy concluded that a lack of movie theaters

stateside

actually contributed to delinquency and high labor turnover. The movie

studios and film exhibitors gladly responded to the Navy's call

for new theaters. During the '40s theater builders relied heavily

on concrete since it was the most abundant non-restricted material

available. Thier construction was the same technique used today to

make simple box-like buildings

to house an auditorium. The concrete block walls of the much smaller

auditoriums were often concealed by large curtains. Cinema attendance reached

its all-time

American high in the immediate years following the war, but it was short lived. After the 1940s

ended, everything started to go wrong for the motion picture

industry. .

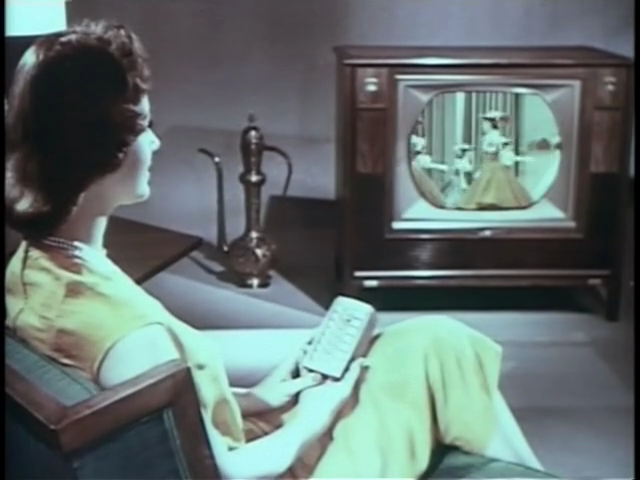

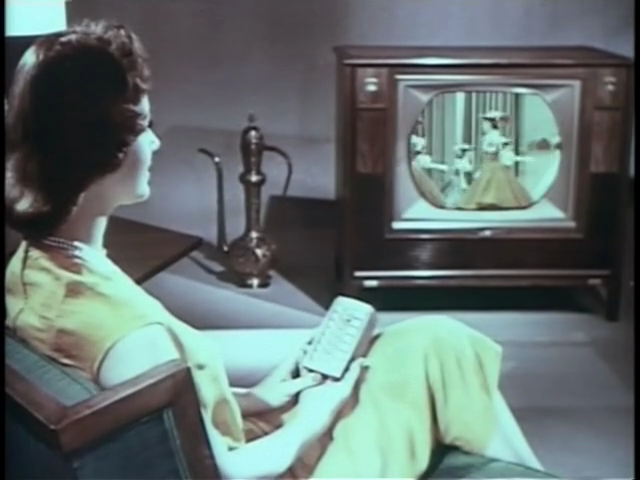

The tide of American consumerism, which had propelled the movie

palaces to prestige and profitability was now contributing to its downfall.

The political phrase, "a chicken in every pot" had morphed

into "a car in every driveway and a television in every living

room." Americans' pursuit of the material good life led them

to a mass exodus to a new suburbian uptopia. Sub-urbanization was facilitated by the federal

government and automakers in Detroit.

The accompanying lifestyle it called

for spelled doom for downtown movie palaces. The growth of the

suburbs and "urban sprawl" began by repaying the returning

World War Two Veterans for their service through subsidies for

interstate construction, the GI Bill, and the FHA mortgage program.

More and more people were moving farther and farther away from

the big cities where the major movie palaces were. The government promoted

this sprawl by the creation of interstate highway construction

that would allow for people to live farther out from the city

yet be able to get to work in relatively short time thanks to

driving on high-speed roads. While most cities had yet to come

to know modern traffic gridlock, it was soon discovered that once

a worker ended his day of work he wanted to leave the city to

go home and stay there until he returned to work the following day. People did not remain in the downtown

district after work to dine or to go to see a movie. Worst of all,

they wanted to sit in their cushy chairs at home and watch that

electronic demon, the Television, in the comfort of thier pajamas at

home. Pictured at right is the 1951 DuMont Royal Sovereign television

that boasts the largest black and white picture tube ever made

at 30" measured diagonally.

The accompanying lifestyle it called

for spelled doom for downtown movie palaces. The growth of the

suburbs and "urban sprawl" began by repaying the returning

World War Two Veterans for their service through subsidies for

interstate construction, the GI Bill, and the FHA mortgage program.

More and more people were moving farther and farther away from

the big cities where the major movie palaces were. The government promoted

this sprawl by the creation of interstate highway construction

that would allow for people to live farther out from the city

yet be able to get to work in relatively short time thanks to

driving on high-speed roads. While most cities had yet to come

to know modern traffic gridlock, it was soon discovered that once

a worker ended his day of work he wanted to leave the city to

go home and stay there until he returned to work the following day. People did not remain in the downtown

district after work to dine or to go to see a movie. Worst of all,

they wanted to sit in their cushy chairs at home and watch that

electronic demon, the Television, in the comfort of thier pajamas at

home. Pictured at right is the 1951 DuMont Royal Sovereign television

that boasts the largest black and white picture tube ever made

at 30" measured diagonally.

In 1948, the Supreme Court finally heard the law suit against

Vertical Integration and declared in what has become known as the

Paramount Decree that the movie industry's vertical

integration was an unlawful monopoly. The court ruled the movie studios

were to sell off

their theater chains. Up to that point, most studio/theater accountants

simply put all of its operations into one pile. While one theater might

be really profitable, some of those profits balanced out the losses

caused by another theater that was loosing money. It was soon

painfully obvious that the movie palaces had been money loosing crown

jewels the studios kept mainly for prestige. they had been allowed to

remain in operation because of the high profits that had come in

from

the smaller suburban theaters. When the studios sold off their theater

chains, the new owners expected to make a profit from their

investments. Theaters

that could not turn a profit for their new

owners were ordered closed and sold off.

This spelled doom to the majority of

the downtown movie palaces. Since most of the theaters were in densely

packed urban areas, the property they resided on had become highly

desired and valuable. At that time, nobody really gave a second thought

about the historical value or the potential contributions these old Movie Palaces

could make to the arts or society. They were simply buildings that not only didn't

make their owners money, but the cost a lot of money to maintain. It only made good business sense to

sell the property for other purposes, which almost always meant the demolishment.

At

the same time, probably the greatest perceived threat to the film

industry at the time was television. Between 1947 and 1957, 90%

of American households acquired a television. While newsreels continued to be made into the 60s, they were a

thing of the past by the mid-1950s; TV news broadcasts meant

people could get the latest news in their homes and much faster whereas the news presented on a newsreel was at least one to two

weeks old when it was shown in the theaters. From the time television

was debuted to the public at the 1939 World's Fair, the TV had

gone from a massive structure with a relatively small imaging

tube to something that a lot of people could watch with relative

ease in a good-sized room in a pretty, yet substantial piece of furniture. As the manufacturing processes switched

from wartime production, televisions were able to be mass-produced

at a cost that became relatively affordable. Radio stations were

now making the transition to television and the choices of what

to watch (and when) greatly improved. While the theaters were

in their dark days, the Golden Age of Television had arrived.

At

the same time, probably the greatest perceived threat to the film

industry at the time was television. Between 1947 and 1957, 90%

of American households acquired a television. While newsreels continued to be made into the 60s, they were a

thing of the past by the mid-1950s; TV news broadcasts meant

people could get the latest news in their homes and much faster whereas the news presented on a newsreel was at least one to two

weeks old when it was shown in the theaters. From the time television

was debuted to the public at the 1939 World's Fair, the TV had

gone from a massive structure with a relatively small imaging

tube to something that a lot of people could watch with relative

ease in a good-sized room in a pretty, yet substantial piece of furniture. As the manufacturing processes switched

from wartime production, televisions were able to be mass-produced

at a cost that became relatively affordable. Radio stations were

now making the transition to television and the choices of what

to watch (and when) greatly improved. While the theaters were

in their dark days, the Golden Age of Television had arrived.

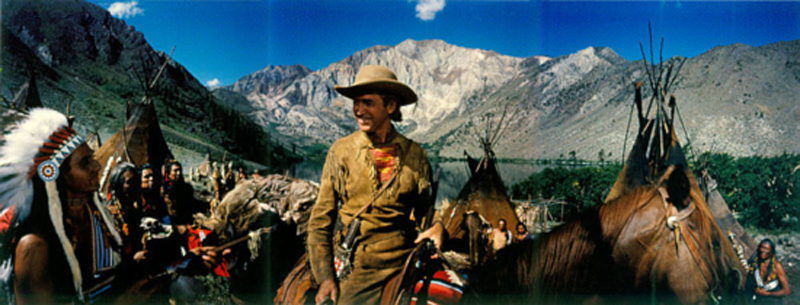

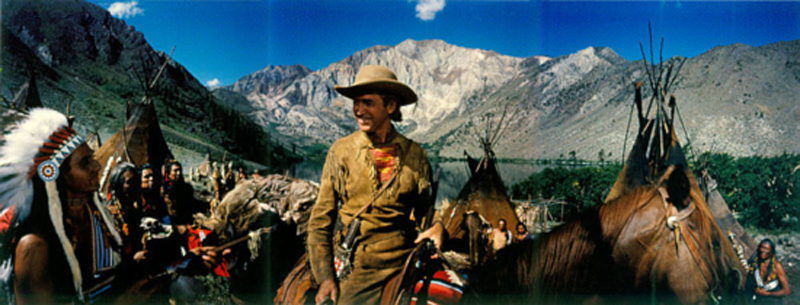

The movie industry was frantic to counter this new competitor,

and in retaliation, they started to renovate their theaters with

such luxuries as air conditioning, large "rocking chair"

seats, wide screen, Cinerama (a frame from "How The West Was Won" is shown above), 3-D motion pictures (audience pictured left), stereophonic

sound, and epic films, all of which meant the renovation of existing

theaters to accommodate a wider screen and thus the destruction

of many elaborate movie palace prosceniums and organ grilles.

One of the attempts to get people back into the cinemas by exhibitors

(and one that makes me grin) was "dish night", a ploy

that was used during the Depression era. For every person that

came to the movie, they would get a piece of dinnerware. The idea

behind it was logical. By getting the whole family out to the

cinema, you'd get a set of dishes for the whole family. You

would return in the subsequent weeks for the other pieces of the

table setting (Dinner plates, roll plates, salad bowls, saucers,

etc.), so this promotion gave the exhibitor a guaranteed number of

patrons for the weeks the promotion was going on. From its all

time high, theater attendance declined to an average of about 42

million patrons per week and continued

to drop. In 1991, average attendance was estimated to be a

dismal 18.9 million per week, compared to its high of 90 million

decades before. Attendance number never really started to increase

until the end of the century.

The movie industry was frantic to counter this new competitor,

and in retaliation, they started to renovate their theaters with

such luxuries as air conditioning, large "rocking chair"

seats, wide screen, Cinerama (a frame from "How The West Was Won" is shown above), 3-D motion pictures (audience pictured left), stereophonic

sound, and epic films, all of which meant the renovation of existing

theaters to accommodate a wider screen and thus the destruction

of many elaborate movie palace prosceniums and organ grilles.

One of the attempts to get people back into the cinemas by exhibitors

(and one that makes me grin) was "dish night", a ploy

that was used during the Depression era. For every person that

came to the movie, they would get a piece of dinnerware. The idea

behind it was logical. By getting the whole family out to the

cinema, you'd get a set of dishes for the whole family. You

would return in the subsequent weeks for the other pieces of the

table setting (Dinner plates, roll plates, salad bowls, saucers,

etc.), so this promotion gave the exhibitor a guaranteed number of

patrons for the weeks the promotion was going on. From its all

time high, theater attendance declined to an average of about 42

million patrons per week and continued

to drop. In 1991, average attendance was estimated to be a

dismal 18.9 million per week, compared to its high of 90 million

decades before. Attendance number never really started to increase

until the end of the century.

The movie palaces not only faced competition from the evil

television, but that also faced direct competition from the theaters

that were popping up in the suburbs and a new form of theater

that would go on to become another great American icon, the Drive-In

Theater. While Drive-In Theaters began prior to World War II, the post-war boom brought in a new golden age of the automobile

and the love of the car sparked a unique fusion of car and cinema.

The Drive-in was very popular with families that could pay a single

car admission for a carload of adults and kids. While the parents

watched the film, the kids could often go and play at a playground

located behind the large parking ground. Couples loved to go to

drive-ins for the "unique" privacy being inside your

own car provided. America's love affair with the drive-in lasted

for about two decades before it began to fall out of favor in

the 1970s. Just like the movie palaces they competed with, the

property they resided on became highly valued real estate and

a lot of them were torn up for other developments.

No

matter what the exhibitors did, it was only minimally effective

in bringing more people to the movie palaces. It was quite apparent

that the days of the large downtown cinema were numbered. One

by one, the big theaters were closing as people either stayed

home or went to smaller theaters located in the sprawling suburbs

that were now being built. Most Palaces were situated on valuable

downtown property. With their owners not being able to pay their

bills, not to mention the large amount of money required to maintain

the palaces, selling off the property to developers was a very

attractive way out of a desperate situation. In 1956, Balaban

and Katz decided to demolish the Paradise Theater in Chicago and

sell the land to a supermarket chain. This was widely considered

to be the start of the darkest days of the Movie Palaces where

the majority of the great houses were destroyed.

No

matter what the exhibitors did, it was only minimally effective

in bringing more people to the movie palaces. It was quite apparent

that the days of the large downtown cinema were numbered. One

by one, the big theaters were closing as people either stayed

home or went to smaller theaters located in the sprawling suburbs

that were now being built. Most Palaces were situated on valuable

downtown property. With their owners not being able to pay their

bills, not to mention the large amount of money required to maintain

the palaces, selling off the property to developers was a very

attractive way out of a desperate situation. In 1956, Balaban

and Katz decided to demolish the Paradise Theater in Chicago and

sell the land to a supermarket chain. This was widely considered

to be the start of the darkest days of the Movie Palaces where

the majority of the great houses were destroyed.

The Paradise Theater was built in the Garfield Park neighborhood

of Chicago, and was billed as the world's most beautiful theater. To

this day it is regarded as one of the greatest movie palaces

ever built. After 3 years of construction, the Paradise opened

for business on 14 September 1928. Its auditorium could hold 3612

patrons in its "atmospheric" hall that was designed

to replicate an open air courtyard with its painted ceiling made

to look like a cloud-filled sky on a warm spring day. The photos

above left and right shown the wonderful exterior and the Paradise's

incredible auditorium. The Paradise put up a fight against its

demolition as the demolition crew discovered that the building

was built substantially better and a lot stronger than the original

blueprint detailed. What was to take a few months took two years

to raze. At one point the demolition foreman committed

suicide because of the stress the project entailed.

One by one, the great Palaces fell. For each of the big theaters

that came down, new smaller theaters would be erected in the fast

growing suburbs. By then, going to the movies had been reduced

from something that was a big outing for the evening to something

that would last for a few hours. Gone were the shorts, the live

acts, the newsreels, and the cartoons. All that was left was the

trailers for coming attractions and the main feature. Part of this was

simple economics. The shorter the program, you could have more showings

in one evening. The exhibitor was only paying for one item to show, yet

his patrons were paying the same admission fee. This meant that with

the old system, you could only have one performance

a night, But with the new system of just the feature film, you could get in

2 or 3 shows in the same auditorium that evening.

The photo displayed

at left is the great silent film actress Gloria Swanson in a staged

photo for LIFE magazine decrying the destruction of the great movie palaces. While

the exact spot she is standing in is not documented, she is standing

in the ruins of the New York Roxy Theatre as it was being demolished

in 1961. All of the ornate plaster and ornamentation is pretty

much gone from the heavily damaged wall, but you can still make

out a magnificent column just to the right of Ms. Swanson, which

indicates to me she is probably standing where the auditorium

used to be. The Roxy was one of the largest palaces to be built

with an extraordinary seating capacity of over 6,000 as shown

on the photo to the right.

The photo displayed

at left is the great silent film actress Gloria Swanson in a staged

photo for LIFE magazine decrying the destruction of the great movie palaces. While

the exact spot she is standing in is not documented, she is standing

in the ruins of the New York Roxy Theatre as it was being demolished

in 1961. All of the ornate plaster and ornamentation is pretty

much gone from the heavily damaged wall, but you can still make

out a magnificent column just to the right of Ms. Swanson, which

indicates to me she is probably standing where the auditorium

used to be. The Roxy was one of the largest palaces to be built

with an extraordinary seating capacity of over 6,000 as shown

on the photo to the right.

Several of the Palaces had extra stories above or around the

theater for retail and office space. This was a godsend to those

theaters because the revenue created by leases helped offset the

loss of revenue of the theater itself. But that did not save them

all. While the buildings were saved, the theaters were not and

the space they occupied was "re-purposed". Some became

department stores, some became churches, and others were gutted

and made into more retail or office space. The worst bastardization

of a Palace occurred with the Michigan Theatre in Detroit. The

theater was only partially gutted and made into a parking lot.

The stage, the movie screen, and even its stage curtain were left

intact and were standing in the shell of the theater for years.

The ornate lobby became

the location for up and down ramps to the various levels of the

parking lot. Read and see more about this theater on my Michigan Theatre Requiem tribute page.

The theaters in the

smaller towns were a lot luckier than their big cousins. Most

were able to stay afloat because they did not have the direct

competition of other theaters in the same town. They were also much

smaller buildings and usual less orante, which meant it was much less

expensive to maintain compared to the true Palaces. Another major

factor

was that in the smaller towns, real estate was a lot more plentiful

and it was much easier to buy a parcel of undeveloped land to

build on rather than having to demolish or renovate an existing

structure. When a small town theater closed, most of them were

simply boarded up for years or even decades waiting to be

rediscovered and used

once more by the community.

The late fifties, the sixties, and the early seventies were

the darkest time for the Palaces. After we lost the greatest as well as the majority

of the Palaces, people began to take notice of what was lost and what we were on the verge of losing forever.

Most metropolitan areas had several big theaters and by the 1970s

all but one or two of them had been demolished, people began to

stand up and fight to preserve what remained.

At the same time, the smaller, less-ornate movie theaters were

undergoing a transformation. Because of the dwindling attendance

figures, most of the theaters built in the suburbs were not being fully

utilised. On average, most of the houses could seat around 1,000

patrons. More than half the seats were being left empty, especially

after the premiere weekend of a film that by contract, the exhibitor

had to show for a number of weeks. Some enterprising film

exhibitioner came up with a novel idea that

allowed him to double his profits with a minimal amount

of investment. The theater would temporarily close while the

auditorium

was divided into two or more viewing halls. Since less than half of the

seats were being filled, this would give the theater owner two 400 or

more seat

auditoriums that could show 2 different movies at the same time. This

in theory would

double their profits. The concept was very sound and it became all the

rage. The next step in this evolution was to go for even more screens.

Doubling led to Triples and Quads that lead to the

modern concept of Multi-plexing.

Multi-Plexing is now the defacto standard in the movie exhibition

business and its concept goes far to further refine and get the most

profit out of film exhibition. Most plexes have at least one ot two

huge auditoriums that hold several hundred people with smaller and

smaller auditoriums that reduce in size to a where the smallest

could accomodate fewer than 50 patrons. The big halls are used to show

the latest blockbuster from Hollywood that's all the rage. In

getting those blockbusters, the exhibitors still have to sign

agreements that

force them to show that particular film for a certain amount of weeks,

long before it's known if the film is going to be hit or a flop.

The one thing that is not usually dictated is in how large an

auditorium the film is

shown. This allows the exhibitor to place the film in

the right-sized

auditorium. So when he demand for tickets goes down, the film moves to

a smaller auditorium until the contract to show it is expired. Most

contracts also do not require the film be shown all day, so things like

children's matinees can be shown in the same auditorium with a

different film. With today's

technology, they can easily move the film, at almost a

moment's notice to any auditorium in the multi-plex. That way,

when Rocky 25 comes out, it can get the big hall, while Star Trek 46: The Search for a Good Script

fulfills its contractual agreement in the smallest auditorium available

while that one die-hard Trekkie looks on by his or her self.

Here in

Atlanta Georgia there is no longer a single screen full-time

motion

picture

theater in operation. Almost every theatre that is more that 25

years

old is no longer in operation. When

this article was written in 1996, there were only three houses older

than thirty years of age. When this was revised in November of 2010,

there are

only five motion picture houses still in existance that date back to

prior to 1990 in the Atlanta area: The Fox Theatre, a true 1929

movie palace is now an omnibus venue that only shows movies in the

summer; the Garden Hills Cinema was shuttered in 2008 but still is

intact; the Plaza Theater in the Midtown district is now operating as a

non-profit independent "art" film house

that was twinned in the late 1980s; The former AMC Northlake 8

multiplex was recently renovated and made

into the "Movie Tavern" a cinema & drafthouse style theater showing

first-run movies;and the "Earl Smith" Strand Theater on the Square in

Marietta. The Strand completed an intensive multi-million dollar

restoration in 2009 and like the Fox, is now an omnibus theater but

unlike the Fox, it regularly screens films. Of the 20-30 movie

theaters

that once were located in metropolitan Atlanta, only 5

remain!

In

2013, movie exhibitors have a new issue to contend with. The Motion

Picture industry is making a huge transition, started by George Lucas

in 1999 with Star Wars I: The Pantom Menace. the film was partially

shot on high-definition video and shown in select theaters via video

projection rather than by film projection. Fourteen years later, 4K and

6K video are rapidly replacing film as the preferred way to present

film. Films can be sent via the Internet through encryption to the

various exhibitioners, totally eliminating local film exchange

distributors. Gone are the days of broken film and hasty edits to put

it back together. Gone are rewinding huge reels or spools of film. In

its place is a rather small DLP "digital" projector (shown at

right). But just as the film projectors when new were rather

expensive, so are the video projectors and support equipment needed to

replace the old ways. I believe it costs around $50,000 and goes

up per auditorium to make the conversion and for some exhibitors that

are living on a close edge between success and failure, that is an

insurmountable fee.

In

2013, movie exhibitors have a new issue to contend with. The Motion

Picture industry is making a huge transition, started by George Lucas

in 1999 with Star Wars I: The Pantom Menace. the film was partially

shot on high-definition video and shown in select theaters via video

projection rather than by film projection. Fourteen years later, 4K and

6K video are rapidly replacing film as the preferred way to present

film. Films can be sent via the Internet through encryption to the

various exhibitioners, totally eliminating local film exchange

distributors. Gone are the days of broken film and hasty edits to put

it back together. Gone are rewinding huge reels or spools of film. In

its place is a rather small DLP "digital" projector (shown at

right). But just as the film projectors when new were rather

expensive, so are the video projectors and support equipment needed to

replace the old ways. I believe it costs around $50,000 and goes

up per auditorium to make the conversion and for some exhibitors that

are living on a close edge between success and failure, that is an

insurmountable fee.

While the smaller single-screen theaters and now even the

Multiplexes are shutting their doors, we are at least blessed that we

still have a handful of the grand

movie palaces in existance. After people realized their historical and

architectural importance, great strives have been made to save

these true treasures.A lot of creative

thought went into how to revitalize the palaces and make them viable in

today's world. Most are becoming omnibus venues presenting

a wide range of different performances. Some have become places of

worship, while others became dinner theaters or homes for local

performing art groups. Regardless of

what the Palaces have become, they all have a common theme of

preserving

one of the most unique pieces of Americana alive for year to come.

In

the begining, "Moving Pictures", now more commonly known as Motion

Pictures or simply "The Movies" were developed by many people in

many countries with the

major innovators being in the United States and France. Here in the

United States,

moving pictures were mainly pioneered by Thomas Edison's company, best

known for

his development of the electric light bulb and phonograph. His

company was the first to demonstrate moving pictures to the public

in the Americas. His

early experiments followed the same pattern as his phonograph,

with the pictures recorded on to a wax cylinder.

In

the begining, "Moving Pictures", now more commonly known as Motion

Pictures or simply "The Movies" were developed by many people in

many countries with the

major innovators being in the United States and France. Here in the

United States,

moving pictures were mainly pioneered by Thomas Edison's company, best

known for

his development of the electric light bulb and phonograph. His

company was the first to demonstrate moving pictures to the public

in the Americas. His

early experiments followed the same pattern as his phonograph,

with the pictures recorded on to a wax cylinder.  Edison's earliest

films lasted for about 20 seconds or less because of the amount

of film you could put into the camera. They were first demonstrated

to the public in 1893 at the Chicago World's Fair. By the following

year, a "Kinetoscope Parlor" opened in New

York, with ten machines showing different films. At right is an

early Edison film from the same time period that has been converted to an animated

GIF. "

Edison's earliest

films lasted for about 20 seconds or less because of the amount

of film you could put into the camera. They were first demonstrated

to the public in 1893 at the Chicago World's Fair. By the following

year, a "Kinetoscope Parlor" opened in New

York, with ten machines showing different films. At right is an

early Edison film from the same time period that has been converted to an animated

GIF. " As the technology

progressed and longer moves could be made, they began to tell

short stories, but even then, they lasted just a few minutes in length. Kinetoscope parlors

sprang up all over the country and rows of Kinetoscopes were added

to existing entertainment venues like penny arcades. Operators

attempted to attract customers through sidewalk barkers and displays set up in their

wide entranceways.

It became an

enduring feature of movie theater construction still employed

today.

As the technology

progressed and longer moves could be made, they began to tell

short stories, but even then, they lasted just a few minutes in length. Kinetoscope parlors

sprang up all over the country and rows of Kinetoscopes were added

to existing entertainment venues like penny arcades. Operators

attempted to attract customers through sidewalk barkers and displays set up in their

wide entranceways.

It became an

enduring feature of movie theater construction still employed

today.

The first major step to that goal was taking the movies out of the

"flea pits"

and placing them into proper theaters that befitted the patronage

of refined gentlemen and ladies. Moving into

converted opera houses and purpose-built theaters did a lot to achieve

that

goal. Built in 1902, Tally's "Electric" Theatre in Los Angeles (shown at left) was

the first permanent structure devoted entirely to movies. Audiences immediately preferred the

comfortable, clean, and well-appointed surroundings of a proper

theater. They theaters also featured better-quality musical

accompaniments and even well-dressed ushers to assist patrons.

The first major step to that goal was taking the movies out of the

"flea pits"

and placing them into proper theaters that befitted the patronage

of refined gentlemen and ladies. Moving into

converted opera houses and purpose-built theaters did a lot to achieve

that

goal. Built in 1902, Tally's "Electric" Theatre in Los Angeles (shown at left) was

the first permanent structure devoted entirely to movies. Audiences immediately preferred the

comfortable, clean, and well-appointed surroundings of a proper

theater. They theaters also featured better-quality musical

accompaniments and even well-dressed ushers to assist patrons.  The

Regent (shown at left) was acknowledged as America's first motion picture

palace. Built for and operated by Jacob Fabian, it opened in Paterson,

New Jersey on September 14, 1914. The Regent was located

in a working class neighborhood up-town from the "legitimate" theater

district and stood between Old Union Street (which was later renamed

World Vet's Place in 1959) and Hamilton Street. As it was being

constructed, a majority of people believed that the huge cost of the

building's construction would prove to be a great liability. To that